- What is a service worker

- The service worker life cycle

- Prerequisites

- Register a service worker

- Install a service worker

- Cache and return requests

- Update a service worker

- Rough edges and gotchas

- Learn more

Rich offline experiences, periodic background syncs, push notifications—functionality that would normally require a native application—are coming to the web. Service workers provide the technical foundation that all these features rely on.

What is a service worker

A service worker is a script that your browser runs in the background, separate from a web page, opening the door to features that don’t need a web page or user interaction. Today, they already include features like push notifications and background sync. In the future, service workers might support other things like periodic sync or geofencing. The core feature discussed in this tutorial is the ability to intercept and handle network requests, including programmatically managing a cache of responses.

The reason this is such an exciting API is that it allows you to support offline experiences, giving developers complete control over the experience.

Before service worker, there was one other API that gave users an offline experience on the web called AppCache. There are a number of issues with the AppCache API that service workers were designed to avoid.

Things to note about a service worker:

- It’s a JavaScript Worker, so it can’t access the DOM directly. Instead, a service worker can communicate with the pages it controls by responding to messages sent via the postMessage interface, and those pages can manipulate the DOM if needed.

- Service worker is a programmable network proxy, allowing you to control how network requests from your page are handled.

- It’s terminated when not in use, and restarted when it’s next needed, so you cannot rely on global state within a service worker’s

onfetchandonmessagehandlers. If there is information that you need to persist and reuse across restarts, service workers do have access to the IndexedDB API. - Service workers make extensive use of promises, so if you’re new to promises, then you should stop reading this and check out Promises, an introduction.

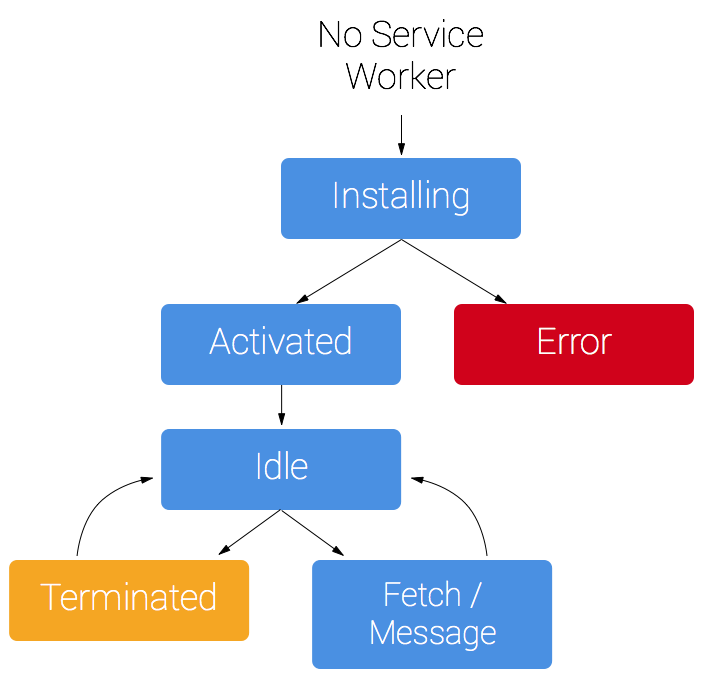

The service worker life cycle

A service worker has a lifecycle that is completely separate from your web page.

To install a service worker for your site, you need to register it, which you do in your page’s JavaScript. Registering a service worker will cause the browser to start the service worker install step in the background.

Typically during the install step, you’ll want to cache some static assets. If all the files are cached successfully, then the service worker becomes installed. If any of the files fail to download and cache, then the install step will fail and the service worker won’t activate (i.e. won’t be installed). If that happens, don’t worry, it’ll try again next time. But that means if it does install, you know you’ve got those static assets in the cache.

When installed, the activation step will follow and this is a great opportunity for handling any management of old caches, which we’ll cover during the service worker update section.

After the activation step, the service worker will control all pages that fall under its scope, though the page that registered the service worker for the first time won’t be controlled until it’s loaded again. Once a service worker is in control, it will be in one of two states: either the service worker will be terminated to save memory, or it will handle fetch and message events that occur when a network request or message is made from your page.

Below is an overly simplified version of the service worker lifecycle on its first installation.

Prerequisites

Browser support

Browser options are growing. Service workers are supported by Chrome, Firefox and Opera. Microsoft Edge is now showing public support. Even Safari has dropped hints of future development. You can follow the progress of all the browsers at Jake Archibald’s is Serviceworker ready site.

You need HTTPS

During development you’ll be able to use service worker through localhost, but to deploy it on a site you’ll need to have HTTPS setup on your server.

Using service worker you can hijack connections, fabricate, and filter responses. Powerful stuff. While you would use these powers for good, a man-in-the-middle might not. To avoid this, you can only register service workers on pages served over HTTPS, so we know the service worker the browser receives hasn’t been tampered with during its journey through the network.

GitHub Pages are served over HTTPS, so they’re a great place to host demos.

If you want to add HTTPS to your server then you’ll need to get a TLS certificate and set it up for your server. This varies depending on your setup, so check your server’s documentation and be sure to check out Mozilla’s SSL config generator for best practices.

Register a service worker

To install a service worker you need to kick start the process by registering it in your page. This tells the browser where your service worker JavaScript file lives.

1 | if ('serviceWorker' in navigator) { |

This code checks to see if the service worker API is available, and if it is, the service worker at /sw.js is registered once the page is loaded.

You can call register() every time a page loads without concern; the browser will figure out if the service worker is already registered or not and handle it accordingly.

One subtlety with the register() method is the location of the service worker file. You’ll notice in this case that the service worker file is at the root of the domain. This means that the service worker’s scope will be the entire origin. In other words, this service worker will receive fetch events for everything on this domain. If we register the service worker file at /example/sw.js, then the service worker would only see fetch events for pages whose URL starts with /example/ (i.e. /example/page1/, /example/page2/).

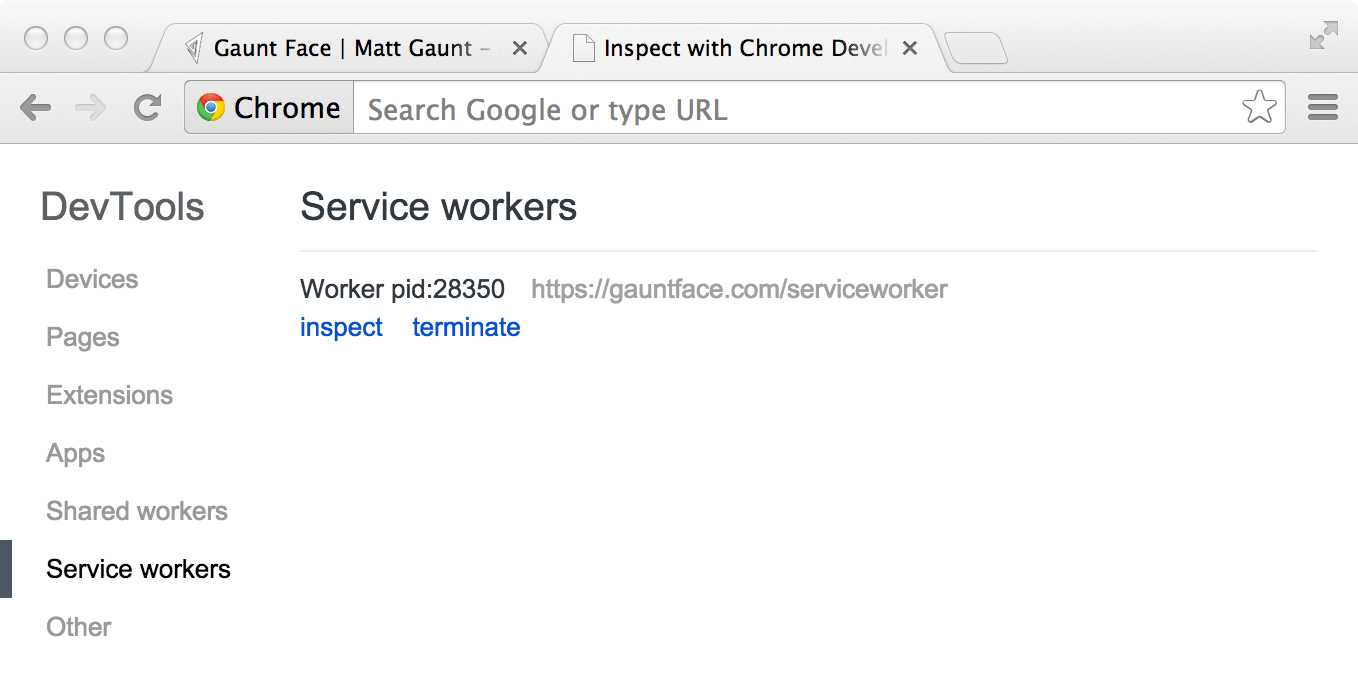

Now you can check that a service worker is enabled by going to chrome://inspect/#service-workers and looking for your site.

When service worker was first being implemented, you could also view your service worker details through chrome://serviceworker-internals. This may still be useful, if for nothing more than learning about the life cycle of service workers, but don’t be surprised if it gets replaced completely by chrome://inspect/#service-workers at a later date.

You may find it useful to test your service worker in an Incognito window so that you can close and reopen knowing that the previous service worker won’t affect the new window. Any registrations and caches created from within an Incognito window will be cleared out once that window is closed.

Install a service worker

After a controlled page kicks off the registration process, let’s shift to the point of view of the service worker script, which handles the install event.

For the most basic example, you need to define a callback for the install event and decide which files you want to cache.

1 | self.addEventListener('install', function(event) { |

Inside of our install callback, we need to take the following steps:

- Open a cache.

- Cache our files.

- Confirm whether all the required assets are cached or not.

1 | var CACHE_NAME = 'my-site-cache-v1'; |

Here you can see we call caches.open() with our desired cache name, after which we call cache.addAll() and pass in our array of files. This is a chain of promises (caches.open() and cache.addAll()). The event.waitUntil() method takes a promise and uses it to know how long installation takes, and whether it succeeded or not.

If all the files are successfully cached, then the service worker will be installed. If any of the files fail to download, then the install step will fail. This allows you to rely on having all the assets that you defined, but does mean you need to be careful with the list of files you decide to cache in the install step. Defining a long list of files will increase the chance that one file may fail to cache, leading to your service worker not getting installed.

This is just one example, you can perform other tasks in the install event or avoid setting an install event listener altogether.

Cache and return requests

Now that you’ve installed a service worker, you probably want to return one of your cached responses, right?

After a service worker is installed and the user navigates to a different page or refreshes, the service worker will begin to receive fetch events, an example of which is below.

1 | self.addEventListener('fetch', function(event) { |

Here we’ve defined our fetch event and within event.respondWith(), we pass in a promise from caches.match(). This method looks at the request and finds any cached results from any of the caches your service worker created.

If we have a matching response, we return the cached value, otherwise we return the result of a call to fetch, which will make a network request and return the data if anything can be retrieved from the network. This is a simple example and uses any cached assets we cached during the install step.

If we want to cache new requests cumulatively, we can do so by handling the response of the fetch request and then adding it to the cache, like below.

1 | self.addEventListener('fetch', function(event) { |

What we are doing is this:

- Add a callback to

.then()on thefetchrequest. - Once we get a response, we perform the following checks:

- Ensure the response is valid.

- Check the status is

200on the response. - Make sure the response type is

basic, which indicates that it’s a request from our origin. This means that requests to third party assets aren’t cached as well.

- If we pass the checks, we clone the response. The reason for this is that because the response is a Stream, the body can only be consumed once. Since we want to return the response for the browser to use, as well as pass it to the cache to use, we need to clone it so we can send one to the browser and one to the cache.

Update a service worker

There will be a point in time where your service worker will need updating. When that time comes, you’ll need to follow these steps:

- Update your service worker JavaScript file. When the user navigates to your site, the browser tries to redownload the script file that defined the service worker in the background. If there is even a byte’s difference in the service worker file compared to what it currently has, it considers it new.

- Your new service worker will be started and the

installevent will be fired. - At this point the old service worker is still controlling the current pages so the new service worker will enter a

waitingstate. - When the currently open pages of your site are closed, the old service worker will be killed and the new service worker will take control.

- Once your new service worker takes control, its

activateevent will be fired.

One common task that will occur in the activate callback is cache management. The reason you’ll want to do this in the activate callback is because if you were to wipe out any old caches in the install step, any old service worker, which keeps control of all the current pages, will suddenly stop being able to serve files from that cache.

Let’s say we have one cache called 'my-site-cache-v1', and we find that we want to split this out into one cache for pages and one cache for blog posts. This means in the install step we’d create two caches, 'pages-cache-v1' and 'blog-posts-cache-v1' and in the activate step we’d want to delete our older 'my-site-cache-v1'.

The following code would do this by looping through all of the caches in the service worker and deleting any caches that aren’t defined in the cache allowlist.

1 | self.addEventListener('activate', function(event) { |

Rough edges and gotchas

This stuff is really new. Here’s a collection of issues that get in the way. Hopefully this section can be deleted soon, but for now these are worth being mindful of.

If installation fails, we’re not so good at telling you about it

If a worker registers, but then doesn’t appear in chrome://inspect/#service-workers or chrome://serviceworker-internals, it’s likely failed to install due to an error being thrown, or a rejected promise being passed to event.waitUntil().

To work around this, go to chrome://serviceworker-internals and check “Open DevTools window and pause JavaScript execution on service worker startup for debugging”, and put a debugger statement at the start of your install event. This, along with Pause on uncaught exceptions, should reveal the issue.

The defaults of fetch()

No credentials by default

When you use fetch, by default, requests won’t contain credentials such as cookies. If you want credentials, instead call:

1 | fetch(url, { |

This behaviour is on purpose, and is arguably better than XHR’s more complex default of sending credentials if the URL is same-origin, but omitting them otherwise. Fetch’s behaviour is more like other CORS requests, such as <img crossorigin>, which never sends cookies unless you opt-in with <img crossorigin="use-credentials">.

Non-CORS fail by default

By default, fetching a resource from a third party URL will fail if it doesn’t support CORS. You can add a no-CORS option to the Request to overcome this, although this will cause an ‘opaque’ response, which means you won’t be able to tell if the response was successful or not.

1 | cache.addAll(urlsToPrefetch.map(function(urlToPrefetch) { |

Handling responsive images

The srcset attribute or the <picture> element will select the most appropriate image asset at run time and make a network request.

For service worker, if you wanted to cache an image during the install step, you have a few options:

- Install all the images that the

<picture>element and thesrcsetattribute will request. - Install a single low-res version of the image.

- Install a single high-res version of the image.

Let’s assume you go for the low res version at install time and you want to try and retrieve higher res images from the network when the page is loaded, but if the high res images fail, fallback to the low res version. This is fine and dandy to do but there is one problem.

If we have the following two images:

| Screen Density | Width | Height |

|---|---|---|

| 1x | 400 | 400 |

| 2x | 800 | 800 |

In a srcset image, we’d have some markup like this:

1 | <img src="image-src.png" srcset="image-src.png 1x, image-2x.png 2x" /> |

If we are on a 2x display, then the browser will opt to download image-2x.png, if we are offline you could .catch() this request and return image-src.png instead if it’s cached, however the browser will expect an image that takes into account the extra pixels on a 2x screen, so the image will appear as 200x200 CSS pixels instead of 400x400 CSS pixels. The only way around this is to set a fixed height and width on the image.

1 | <img src="image-src.png" srcset="image-src.png 1x, image-2x.png 2x" |

For <picture> elements being used for art direction, this becomes considerably more difficult and will depend heavily on how your images are created and used, but you may be able to use a similar approach to srcset.

Learn more

There is a list of documentation on service worker being maintained at https://jakearchibald.github.io/isserviceworkerready/resources that you may find useful.

Source:

https://developers.google.com/web/fundamentals/primers/service-workers